And why it needs to be uncomfortable

Sean D’Antoni

Metadata

Urban Eidos Volume 2 (2024), pages 3–4

| Journal-ISSN: | 2942-5131 |

| DOI (PDF): | https://doi.org/10.62582/RNRI95107P |

| DOI (online): | https://doi.org/10.62582/RNRI95107 |

Abstract

Walter Benjamin told us about what art had lost in the course of its reproducibility. In this article I want to go into more detail about the characteristics that art had to make use of in order to preserve its balance and eventually become what we know it as today. Modern Art. I limit myself to those aspects that, in my opinion, not only determine the art world alone, but also penetrate deeply into the ‘roots of society’ and serve as extremely clear examples.

Introduction

„The art of what had become a historical modernity had enormous areas of friction that the artists worked through. They always wanted something new, different, and if possible, something revolutionary. “ [1]

This is an answer from the AI-powered browser, Brave, on the topic of “Modern Art.” And you can also find similar sentences on Wikipedia. „Modern Art is a relatively vague but common colloquial term for the avant-garde art of the 20th century, although this term has been in use since the late 18th century.” [2]

In a way, modern art often seems to be against something. However, I do not want to define what is avant-garde and what is not. After studying art, I can only confirm that as an artist you are often perceived as ’different‘. According to the countless search engines on the Internet, it is exactly what you would expect from a modern artist today.

The development from the artist as a universal genius in the 16th century to the role of the misunderstood rebel from the 19th century onwards reflects, like no other movement, the changes in economics, politics and, above all, perception[3]. If art’s answer to the upheavals of the last few centuries is “modern art,” then what could have been the question that led to such an answer? As Benjamin I will start my search in the spheres of economy, the dominant substructure of our time.

The Great Anonymization

If goods are produced without first knowing to whom these goods will be sold, this is production for an anonymous market. The nature of an anonymous market becomes particularly clear in the historical context of industrialization.

Where previously production only began as soon as a direct order was received, it soon became more profitable to produce larger quantities of goods without having to wait

for corresponding orders. Fig. 1 shows a handmade chair from the 16th century with a blazon incorporated. As the economic pace and with it the pressure to sell more goods increases rapidly, external communication directed at new potential customers must also accelerate. Fig. 2 shows a full stock of chairs inside a typical IKEA market. From 1875 onwards, in order to keep up with the immense speed of production, the first registered trademarks, logos, posters and packaging designs were created, some of which are still familiar to us today.[4]

.

.

Fig. 3: Logo of Bass Brewery’s Pale Ale from 1876.

Fig. 4: A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Manet, 1882.

Now the brands can thrive

Brands have existed as long as there has been retail. Sealed sacks, brandings, and labelled clay pots are just a few examples of how brands were used in the ancient economy. Today, a brand still serves as a means of differentiation. A feeling of individuality should clearly distinguish the product from other products.

What has changed since industrialization, however, are the standards. An unprecedented scope now makes it possible to create “a market” as we know it today. As an intangibly large, anonymized market that can only be reached through a wide variety of media, whose individual participants initially only exist hypothetically. This means that the market also becomes a space of assumptions and guesses.

In

In

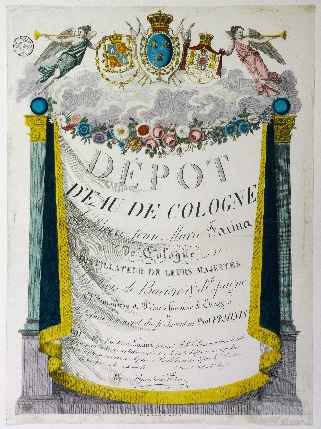

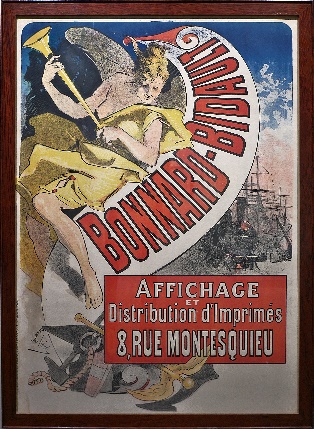

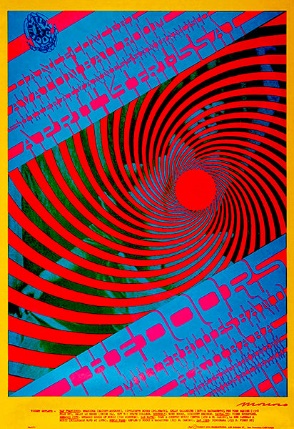

Fig. 5: Development of poster aesthetics between 1833 and 1992.

this speculative space, the brand itself or, more precisely, the image of a brand must now take over the communication for the seller. The sheer size of a market now makes it impossible to speak to every individual in it personally. The image should therefore speak for itself and create an appearance that represents the entirety of a brand or company to the outside world. In 1967, Guy Debord described the so-called spectacle and defined it, among other things, as “capital accumulated to the point that it becomes images. [5]

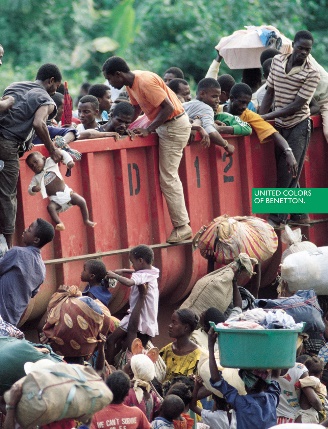

The posters in Fig. 3 show a chronological progression from left to right. While in 1833, full emphasis was placed on a detailed text to advertise a perfume, Benetton lets provocative images speak for themselves. The power of the images, with the company logo placed directly in front of them, creates a more than sufficient connection to the brand. Brands should now not only set boundaries, but also create their own inner world, embodying an image that encourages as many potential buyers as possible to buy.

The effect on politics

The anonymity of the new markets not only turns the goods manufacturers into advertisers. The anonymous market is gradually transforming entire societies into ‘advertisers’. It is no coincidence that the advertising industry can thrive particularly well, influenced by the cultural legacy of enlightened humanism, which places the freely deciding human being at the centre of all morals and ethics. It is precisely the “advertising itself” that emphasizes the basic humanistic ideas in economics, and even seems to automatically carry them within itself. Humanism in the market economy should mean that people themselves decide what a “good” product is and not God or any ruler. This means that the product that is bought the most is automatically rated as the best. Due to the sheer size of the anonymous market, “advertisement” acts as a sovereign and reliable benchmark for democratic economic processes.

In the course of the English Revolution of 1688, Adam Smith, referred to the improved living conditions of the last 100 years and wrote in 1776: “A person who can acquire no property, can have no other interest but to eat as much, and to labour as little as possible.” [6]

While Smith tries to protect the new standard of living above all from the monarchy, he interweaves the basic humanistic ideas of his time with the image of a liberalizing market economy.

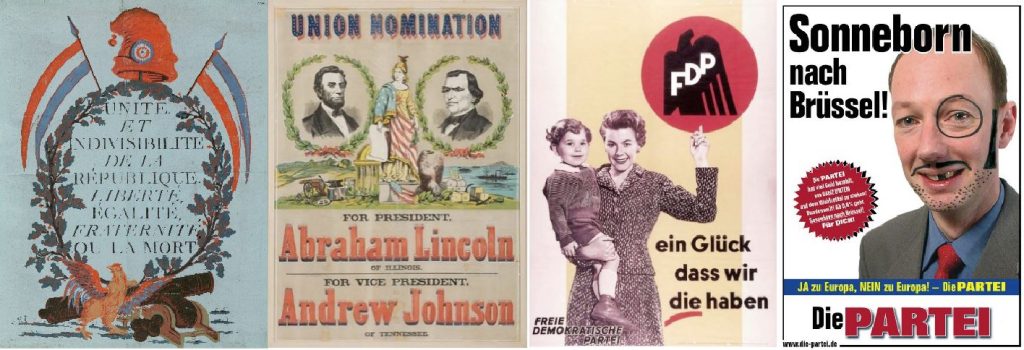

Perhaps that is why it seems so natural to us today that a political party uses the same methods to woo its voters as a company woos its customers. Since the 18th century, the look of political election posters has been much closer to that of posters in the world of goods. Fig. 4 shows significant similarities to posters from the advertising industry. Today, parties pay for advertising on social media just as companies do. Electable representatives, political content and goods are all traded with the same liberal market logic, and the impression is that political contents are just like goods in the supermarket. Prefabricated and tightly packaged, they can be conveniently selected without requiring any deeper participation or a sense of partaking.

The party thus turns itself into a mere commodity that promises a ‘better life’ in the sense of convenience. However, if you really want to take part in politics as a citizen, it quickly becomes clear that the general conditions within an anonymous market are more than a hindrance. Communication between citizens and political representatives largely takes place indirectly via mass media, and even among the respective voter groups themselves there is virtually no local place for political encounters and exchanges. Personal interfaces at an eye level are now an unprofitable affair and are therefore rarely guaranteed. In contrast, the age of political talk shows, in which messages can be spread much more effective, is flourishing. An exchange does not take place directly, yet conveys this because in almost every aspect of our lives it seems self-evident to us that the images of people portrayed in the advertising world already speak for us, the customer. There are no communitas, but rather mass media terminals for messages that guide and anticipate communication in our name, the market.

Modern Art and the quest for real experience

It is therefore no coincidence that the first thinkers and discoverers of this ‘framework’ came from the arts. In his essay Modernist Painting from 1960, Clement Greenberg portrays Kant as the first real modernist who first subjected the discipline of criticism to his own criticism and uses this to further explain what we now perceive as “modern art”. Little by little, according to Greenberg, with Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason the demand for justification of all formal social activities became louder and louder, until finally even areas that were far from philosophy were entrusted with interpreting Kant’s self-criticism.

“At first glance it seems as if the arts were in the same situation as religion. Since the Enlightenment denied them any tasks to which they could have devoted themselves seriously, it seemed as if they should simply be equated with entertainment and that this in turn, like religion, should be equated with a therapeutic procedure. The arts could only protect themselves from such devaluation by providing proof that the experience they create has its own value and cannot be gained from any other activity. […]. Self-criticism now had the task of excluding from the effects of a particular art all those which were possibly due to the medium of another. This means that every art should keep itself ‘pure’ and base the criteria of its quality and independence on this ‘purity’.” [7]

Fig. 7: Composition with Yellow, Red, Black, Blue,

and Gray, Mondrian, 1920.

Almost simultaneously, with the advent of the great poster era in the 19th century, art finally split into two fundamental, seemingly completely incompatible disciplines: ‘free art’ and ‘design’. While the industry places clear demands and conditions on the designer, free art is forced to distance itself from everything that could distort or illusion the experience of a specific art in the sense of self-definition. This laid the foundations of modern art. Suddenly, for example, realistically painted pictures are considered illusionistic because the medium, the canvas, is concealed by the art itself. Art is hidden through art and so modern art in turn wants to draw attention to art through art. The two-dimensionality of the surface of a canvas can no longer simply be ignored, but should be shamelessly and disillusionedly displayed as a natural condition of the medium. Artists like Mondrian, Rothko and Pollock completely do away with the understanding of art at the time. And pave the way for Pop Art.

A unique abyss opens between the anonymous market and modern art. While the value of an experience in the context of the anonymous market is presented by example – think of the happy faces of those who fabulously demonstrate the advantages of a product to us in commercials – modern art must separate every experience from all preexisting evaluations to make it possible to experience it in an unadulterated way. Modern art, with its demands, is therefor also a search for the self-specific value of an experience. This search is further intensified by the decline of the aura[8], the aloofness, authenticity, and uniqueness of a work of art, described by Benjamin.

So, when a society bases its pool of experience largely on pre lived experiences, because the supposedly ‘humanistic economy’ particularly favours this type of communication, and at the same time allows a group to emerge within this society that, conversely, seeks the exact opposite, this is initially a particularly ironic joke, and even more so, it is completely understandable that terms such as “avant-garde” have found their way into the everyday language since 1920. [9]

Sartre would later write down a sentence that was important for the art world in his essay Being and Nothingness in 1942. Sartre first describes the so-called bad faith “mauvaise foi”[10] as self-deception about reality in two forms. The first is that you mistakenly believe that you are not what you actually are. The second is to objectify yourself (e.g. equate yourself with a job or an ideal) and thereby deny freedom.

This essentially means that humans assume that their social role corresponds to their human existence. Living a life defined by one’s job, social status, or economic ideal is at the heart of “insincerity,” the state in which people cannot move beyond their situation to see what they (as human beings) are and more importantly, what they are not exclusively (waiters, grocers, artists, philosophers, etc.). For Sartre, freedom is a state of mind in which we can become anything we desire in relation to any given situation. However, giving meaning to situations independently is a laborious act, the feeling of which Sartre describes impressively in his novel Nausea.

There can be a free for-itself only as engaged in a resisting world. The Situation. Outside of this engagement the notions of freedom, of determination, of necessity lose all meaning. [11]

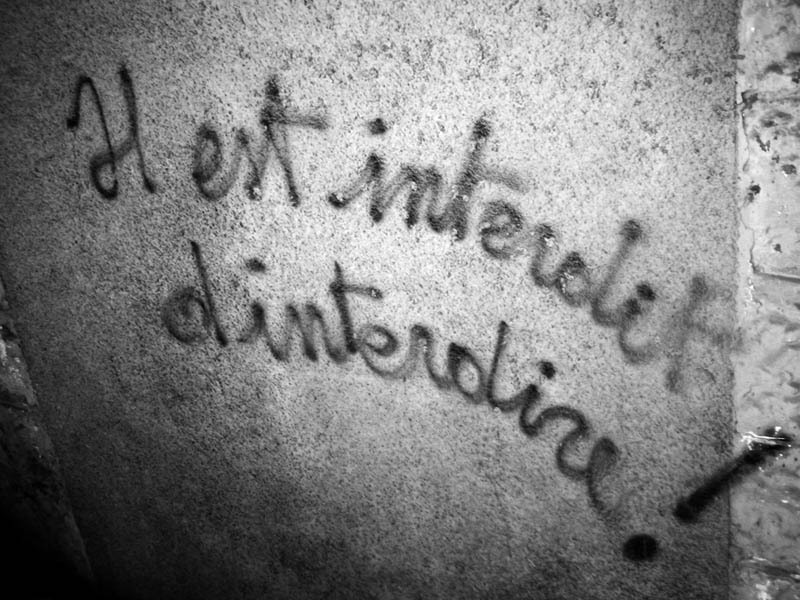

What Sartre defined as a situation thus became one of the most important instruments of modern art, especially for the group of Situationists International, which tried to create situationist art. An art that should suddenly throw the viewer into a wide variety of situations, between everyday life and absurdity, aiming for the ‘liberation from the anticipated’. “The World as a Labyrinth was an exhibition planned by the Situationist International to open at the Stedelijk on May 30, 1960. Rather than curators selecting completed works of art to fill the galleries, artists were to be given space in which to create a site-specific intervention. Despite the fact that the show was canceled before it opened, the plans laid the groundwork for future ludic exhibitions at the museum with respect to content and exhibition design.” [12]

The artist, filmmaker and co-founder of the Situationist International Guy Debord begins his 1967 manifest The Society of the Spectacle with the momentous words:

„1. The entire life of the societies in which modern conditions of production prevail appears as an enormous collection of spectacles. Everything that was directly experienced has escaped into an imagination

2. The images that have separated themselves from every aspect of life merge into a common course in which the unity of that life cannot be restored. The partially viewed reality unfolds in its own general unity as a separate pseudo-world, an object of mere contemplation. The specialization of the images of the world is found complete in the image world that has become autonomous, in which the lying has lied to itself. The spectacle in general is the concrete inversion of life, the independent movement of the non-living.”[13]

Through Sartre’s influence, modern art felt particularly obliged to reject or question the norms established primarily by the world of advertising in order to protect the self-specific experience of a situation in the name of freedom from an increasingly ‘modelled world’.

Figures

You may include up to 20 figures in your contribution. Please ensure that each figure is numbered and features a descriptive caption. We encourage you to refer to your figures in your body text, e.g. as demonstrated in Fig. 1, we can state that an image is important to convey certain aspects of our argument.

Figure 1: Chair (Sgabello), 16th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art.Credit: The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931.

Figure 2: Armchair (Strandmon), 2024, IKEA Karlsruhe, Germany.

Figure 3: Logo of Bass Brewery’s Pale Ale from 1876.

Figure 4: A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Manet, 1882. (Oil on canvas, 96cm x 130cm, Courtauld Gallery London).

Figure 5.1: Eau de Cologne, c.a. 1830, Pierre Jean Marie Farina.

(Engraving, 56cm x 42.5cm, Musée Carnavalet Histoire de Paris).

Figure 5.2: Bonnard Bidault, ca. 1887, Jules Chéret.

Figure 5.3: Avalon Ballroom, 1967, Victor Moscoso.

License: “This Family Dog Poster image is protected by US and International Copyright Law and © Family Dog 1967 – © Rhino Entertainment 2008, used under license. The image may not be used in any form without expressed written permission from Victor Moscoso at www.victormoscoso.pro”.

Figure 5.4: United Colors of Benetton, 1992, Oliviero Toscani/ Patrick Robert.

(S/S 1992, “Container”, Concept: Oliviero Toscani).

Credit: Patrick Robert/Sygma.

Figure 6.1: Print of the First Republic, 1793.

(58cm x 45cm, Bibliothèque Nationale de France).

Figure 6.2: Lincoln & Johnson, campaign poster, 1864.

Figure 6.3: FDP, campaign poster, 1957.

Credit: Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung, Archiv des Liberalismus, 1969.

Figure 6.4: Die Partei, campaign poster, 2014.

Figure 7: Composition with Yellow, Red, Black, Blue and Gray, Mondrian, 1920.

(Oil on canvas, 91.5cm x 92cm, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Rome)

Figure 8: Situationist graffiti, Menton, France, 2006

(the 1968 slogan Il est interdit d’interdire!, “It is forbidden to forbid!”, with missing apostrophe)

References

Guy Debord (2014), The Society of the Spectacle.

Annotated translation by Ken Knabb, published in 2014 by the Bureau of Public Secrets.

ISBN 978-0-939682-06-5

Adam Smith (1981), An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Reprint. Originally published: Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979. (Glasgow edition of the works and correspondence of Adam Smith; 2).

ISBN 0-86597-006-8

Clement Greenberg (1982), Modernist Painting. Reprinted in Francis Frascina and Chales Harrison edited Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology.

ISBN 0-06-433215-2

Jean-Paul Sartre (1957) Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. Translation published in Great Britain in 1957.

Catalogue No 5973/U

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (2024), Online-Journal, https://stedelijkstudies.com/journal/ludic-exhibitions-at-the-stedelijk-museum-die-welt-als-labyrinth-bewogen-beweging-and-dylaby

Accessed: Mai 28th 2024.

Footnotes

Brave Browser uses an AI powered search engine (2024), on the problems of Modern Art. ↑

Wikipedia entry (2024), on Modern Art. ↑

Walter Benjamin argues in his work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction 1935, that the economic system changes the perception of art. ↑

The Bass Red Triangle was the first trade mark to be registered under the UK’s Trade Marks Registration Act of 1875. ↑

Debord 1967, p. 11. ↑

Smith 1776, p. 387. ↑

Greenberg 1961, p. 6. ↑

According to Benjamin’s definition, the aura of a work of art is unique to the space it is in. ↑

With Marx, the previously military term first entered normal usage. It was quickly taken up by the art world. ↑

Sartre, p. 48. ↑

Sartre, p. 599. ↑

Statement from the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam concerning the 1960 exhibition The World as a Labyrinth. ↑

Debord, p. 2. ↑